In April of 2011, Apple kicked off what would soon become a global and complex series of litigation disputes when it sued Samsung in the US claiming that its line of Galaxy smartphones and tablets infringed upon Apple’s intellectual property and were nothing more than “slavish” copies. As part of its suit, Apple requested a preliminary injunction that would bar Samsung from selling said products in the US.

This past Friday, Judge Lucy Koh denied Apple’s motion for a preliminary injunction.

Apple’s request for a preliminary injunction claimed that Samsung’s products infringed upon Apple’s design patents and that they also copied Apple’s UI, with a specific reference to Apple’s ‘381 patent regarding inertial scrolling.

In any event, let’s dive into the ruling.

For a plaintiff to succeed on a motion for a preliminary injunction, he or she must meet four criteria. First, they must demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits of the underlying litigation. Second, they must establish that they would suffer immediate and irreparable harm if the relief is not granted. Third, they must show that the balance of the hardships between the parties weighs more heavily on them. And fourth, they must show that the granting of a preliminary injunction is in the public interest.

As to the first requirement – establishing a likelihood of success – Apple had to show that it would likely prevail at trial in its effort to prove that Samsung’s accused products infringe upon Apple’s design and utility patents.

As to Apple’s design patents – patents embodying the physical design of the iPhone such as the location of the speaker, the size of the device, it’s rounded corners etc., – Samsung articulated that these patents are invalid to the extent that they encapsulate designs that are functional and not within the confines of a design patent. Put simply, if a design choice is absolutely necessary to properly create a functioning product, it is not so much a design choice as it is choice that must be made in the interest of functionality. Specifically, Samsung argues that all of the design features of the iPhone – its rectangular shape, its rounded corners, its speaker placement, the horizontal shape of the speaker, its black color and border around the screen, the bezel, and the lack of significant ornamentation are all primarily functional and thus make the design patents at issue invalid.

In response, Apple proffered a number of alternative smartphone designs which accomplish the same functions listed above, albeit with different designs. Samsung counters that the alternatives Apple proferred “would adversely affect the utility” of said devices. The Court, however, did not buy into this particular Samsung argument and found a number of examples from Apple of other devices that housed shaper corners and differently shaped speakers etc.

So to that end, the Court found that Samsung did not sufficiently prove that Apple’s design patents were invalid based on functionality.

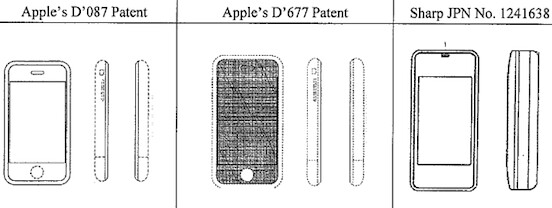

But Samsung objected to Apple’s design patents on other grounds, namely that they were obvious designs. And of course, for a patent to be valid, it must be non-obvious. To this end, Samsung offered up a previous patent from Sharp which, like the iPhone, has a rectangular form factor, rounded corners, a bezel, a similarly horizontal speaker at the top of the device, and an overall minimalistic design. Consequently, the Court found that “an ordinary observer would likely consider the D’087 patent to be substantially the same as the front view of the ‘638 patent” and that the Sharp patent therefore raises legitimate questions as to the validity of the D’087 patent above.

Apple, meanwhile, argues that all the design views of the ‘638 patent must be considered, arguing that there are significant design differences between the two such as the fact that the ‘638 patent shows a screen that can slide upwards to reveal a keyboard underneath.

The Court writes:

Apple, however, cannot compare all views of the ‘638 patent with all views of the D’087 patent because Apple never claimed all views of the D’087 patent… If Apple had wanted to claim the entirety of the article of manufacture, it could have drafted the design patent to include all views. It has not, and the Court therefore should not compare aspects of the design not specifically claimed by the patent.

In sum, the Court found that Samsung was successful in raising substantial questions as to the validity of Apple’s D’087 patent and that Apple was unable to persuade the Court that it would likely succeed at trial in its efforts to uphold the validity of said patent.

As to Apple’s D’677 patent – which describes the design choice of a black transparent and glass-like front surface, the Court ruled that Samsung did not meet its burden of raising substantial questions as to its validity.

“While it may have been technologically possible at the time the D’677 patent was invented to have a flat, black, translucent front screen, this does nothing to explain why it would have been obvious for a designer to have adopted this design choice.” Further, the praise heaped upon the iPhone design when first introduced suggests, the Court writes, that the D’677 parent was not obvious.

Next, the Court considers whether Samsung’s products, in the eyes of an ordinary observer, would likely be deemed substantially the same as Apple’s iPhone.

To this end, the Court finds that an ordinary observer would, in fact, find the Samsung Galaxy S 4G to be substantially the same as the iPhone. The same determination was made regarding the Samsung infuse 4 which the Court ruled likely infringes upon Apple’s D’677 patent.

That notwithstanding, remember that Apple needs to prove that it will suffer irreparable harm if a preliminary injunction is not granted. To this end, Apple argues that it will in that Samsung’s devices will erode Apple’s design and brand distinctiveness and will also result in Apple losing marketshare as a result of Samsung’s infringing products.

The Court, however, notes that Apple was unable to cite any authority on which to rest its argument that the “dilution of design ‘distinctiveness’ establishes irreparable harm.Further, the Court notes that Apple failed to persuasively argue that the proliferation of Samsung products will tarnish its reputation for innovation.

As for irreperable harm, the Court writes that Apple did not establish that it is likely to be irreparably harmed in the absence of an injunction.

Ultimately, the Court finds that Apple has not met its burden of establishing that Samsung’s allegedly infringing products will likely cause Apple irreparable harm. Although Apple and Samsung are direct competitors in the market for new smartphone purchases, and Apple has a right to exclude Samsung from marketing or selling infringing products, both of which are considerations which suggest that there may be irreparable harm in the absence of an injunction, Apple has not provided sufficient evidence to establish more than a mere possibility of future harm. Given the ambiguity of the evidence regarding the importance of design to smartphone purchasers, and the lack of evidence establishing actual consumer confusion, or some other direct or circumstantial evidence that Samsung’s design choices have impacted Apple’s market share or led Apple to lose customers, it is difficult to say that Apple is likely to suffer irreparable harm as a result of Samsung’s infringing conduct.

As for the battle of hardships between the parties, the Court finds that it weighs in favor of Samsung. In other words, the hardship Samsung would suffer as a result of a improperly issued injunction would be greater than what Apple would suffer should they ultimately succeed on the merits when the case goes to trial.

Regarding the public interest requirement, Samsung argues that competition is in the public interest while Apple argues that the protection of intellectual property rights is in the public interest. To this end, the Court finds that the public interest factor “does not weigh strongly in either party’s favor.”

So the Court rules:

“Weighing all of the factors, the Court is left with the firm impression that it would be ‘inequitable for an injunction to issue.’ At this point in the proceedings, although Apple has established a likelihood of success on the merits at trial, there remain close questions regarding infringement of the accused devices, and Samsung has raised substantial questions regarding the validity of the D’087 patent. Moreover, Apple has not yet established a likelihood of irreparable harm, and the balance of the equities weigh in favor of Samsung. Accordingly, the Court DENIES Apple’s motion for a preliminary injunction prohibiting Samsung from making, using, offering to sell, or selling within the United States, or importing into the United States Samsung’s Infuse 4 and Galaxy S 4G.”

The Court also DENIED Apple’s motion to attain a preliminary injunction against Samsung’s Galaxy Tab 10.1 despite the fact that it had a stronger case here for irreparable harm than it did with respect to Samsung’s smartphones. The reason is that the tablet market is essentially a two player market so it’s easier to infer that a Samsung Galaxy Tab sale comes at the expense of an iPad sale.

Nevertheless, Samsung raised questions of validity regarding Apple’s D’899 patent and Apple did not establish that it would likely to succeed at trial.

As for Apple’s ‘381 patent – otherwise known as intertial scrolling – the Court found that Apple is likely to succeed on the merits at trial for the four accused Samsung devices, namely the Infuse 4G, the Galaxy S 4G, the Droid Charge, and the Galaxy Tab 10.1. However, the Court found that Apple is not likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of a preliminary injunction.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.