Marco Ament recently wrote an interesting piece discussing some of the recent hoopla over the iTunes App Store and its ability, or lack thereof, to provide developers with a sustainable income.

Not too long ago, Ged Maheux of Iconfactory wrote that the app store is “broken”, and as an example, he cites the recent experiences his team had with the iPhone game Ramp Champ. Despite spending hundreds of hours developing the game into a extremely polished final product, not to mention a slew of positive product reviews and an aggressive advertising campaign, sales of Ramp Champ got off to a quick start but quickly petered out – leading Maheux to write:

In order for a developer to continue to produce, they must make money. It’s a pretty simple concept and one that tends to get lost in the excitement to write for the iPhone. It’s difficult for me to justify spending 20-50 hours designing and creating new 99¢ levels for Ramp Champ when I could be spending that time on paid client work instead. I would much rather be coming up with the sequel to Space Swarm than drawing my 200th version of a magnifying glass icon.

A fair point, but the relative lack of success for Ramp Champ can’t solely be attributed to the easily drawn conclusion that “the iTunes app store is broken.” On that point, Ament takes Maheux’s theory to task and comes up with the interesting theory that there are, in fact, two separate app stores at work on iTunes, App Store A and App Store B.

App Store A, Ament writes, consist of “simple, shallow games and apps with mass-market appeal.”

Under Ament’s theory, it makes sense to think of the app store as consisting of App Store A and App Store B.

These apps are developed quickly and cheaply, and are rarely updated once their initial popularity (if any) dies down. Very few are priced above $0.99. Impulse-buying is king, with most purchases happening on the phone itself, and most buyers don’t know or cares whether you’re an established developer unless your name begins with “MLB”.

App Store B, on the other hand, consist of “games with more complexity and depth, narrower appeal, longer development cycles, and developer maintenance over the long term.”

Ament writes that more detailed and complex apps, by their very nature, are priced at higher pricepoints and are less likely to be purchased by consumers as impulse buys on the go. Rather, these types of apps tend to be purchased as a result of trusted blog reviews and good ole’ fashioned word of mouth. And it makes sense – unless you’re EA, it’s hard to generate substantial sales for an app priced at $9.99 unless you can tout a number of highly favorable reviews etc. Ament notes that apps that fall into this category “are unlikely to have giant bursts of sales” but “have a much greater chance of building sustained, long-term income.”

Now turning his sites onto Ramp Champ, and using his theory of 2 app stores co-existing side by side under the iTunes umbrella, Ament articulates why the game may not have lived up to developer expectations.

The Iconfactory seems entirely set up for producing excellent apps for App Store B. Their most well-known app, Twitterrific, is solidly in that camp. The problem with Ramp Champ is that they targeted App Store A in gameplay depth and type (which may not have been intentional), and budgeted for App Store A’s expected sales for a hit. But they built, designed, and promoted it as if they were targeting App Store B.

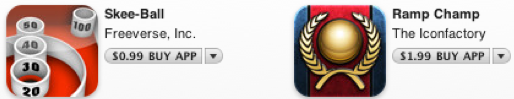

Ament also points out that Ramp Champ’s icon didn’t do a good job of conveying what the app was about, which stands in stark contrast to a Ramp Champ competitor called Skee-Ball, which as luck would have it, has actually preformed rather well on iTunes.

Also problematic, Ament writes, is that Iconfactory chose not to license the name Skee-Ball, which Freeverse obviously chose to do when it released its game of the same name.

Clearly, when you look at the 2 icons above, you instantly know what one app is about while the other (Ramp Champ) could basically be a game about anything. And in the fast moving world of iTunes apps, where customers don’t have the ability to demo apps, a powerful icon and a meaningful title aren’t only important, they’re essential.

Skee-Ball is immediately recognizable, well-known, and obvious. But Ramp Champ looks likely to lose out on nearly every impulse purchase from people who don’t want to spend much time looking into it — which is nearly every buyer for App Store A.

The Iconfactory’s apps are able to compete strongly when people choose apps based on research, reviews, or feature comparisons. But that’s not how App Store A’s customers operate. Whether Ramp Champ is a better game than Skee-Ball is irrelevant to them because they’ll never take the time to find out.

Marco concludes by stating that he’d rather take up a strong position in App Store B, where his app Instapaper does pretty well, then aim for success in the “hit-driven, high-risk, quick-flip requirements of the mass market” that rules over App Store A.

You can check out the entry in its entirety over here.

Mon, Oct 12, 2009

News